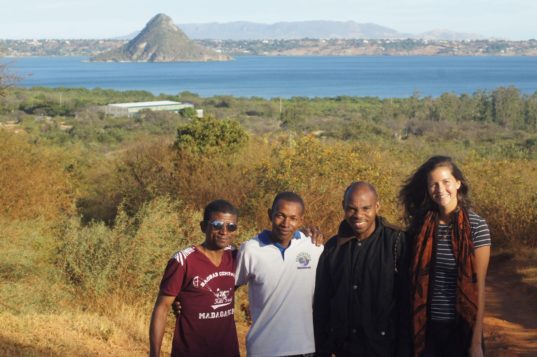

The research team during the trip | Photo: Hope Beatty, Blue Ventures

As we headed out on the bumpy road to Ambolobozobe in the northeast of Madagascar, there was a sense of anticipation. We were going to meet the coastal communities who are successfully managing multiple Locally Managed Marine Areas (LMMAs) as part of our research. As the car wound down the beautiful coastline, I felt motivated to be part of the research team led by Imperial College London researchers in collaboration with Conservation International and the Catholic University in Antananarivo, Madagascar.

The history of LMMAs started with communities in Fiji in the mid 90s and today exceeds 8.3 million km2 and 2.3% of the global ocean area. In Madagascar, the first LMMA (Velondriake) was established shortly after in 2006 with Blue Ventures supporting the village of Andavadoaka in the southwest of the island. Since then the community-led marine management initiative has spread around the country’s coastline increasing to 178 LMMAs supported by 25 NGO partners. Conservation International is one of the supporting NGOs with the Diana region being one of the areas they have supported communities to establish LMMAs.

Our stay in Ambolobozobe village was special as Jaozandry, the president of the village, was the most brilliant host. He welcomed us into his home and shared his stories of the long battle he has had to protect marine resources. As a strong advocate pushing for the new fishing regulations in the LMMA to be legitimized, he was also often a target for certain community member’s frustrations. Jaozandry planned for us to travel out to a nearby island in his Lakana (local wooden sailboat), an honour as he told us as we were the first ‘outsiders’ to be taken to the island. Arriving at the idyllic pristine white sandy beach and beautiful thick dark green vegetation, we stumbled upon an illegal fisher camp with rubbish littered around the scar of the fire and a large turtle carcass.

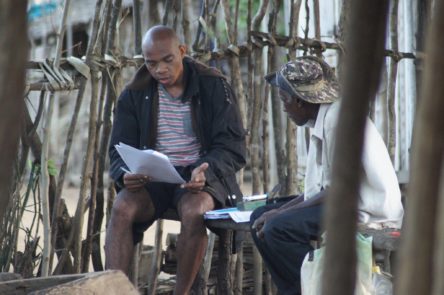

Jaozandry was saddened by the scene but continued with determination to explain to us why the LMMA was so important in bringing together the community. He spoke passionately about how to prevent such events and protect the marine environment for their children to be able to, one day, experience the bountiful marine life including turtles. It is the determination and collective action of community members like Jaozandry who will make this vision a reality – real conservation champions who have the ability to motivate others. Keen to learn what was driving the community to adopt LMMAs, we interviewed community members from four coastal villages including Ambolobozobe village who had adopted this practice. This allowed us to understand what they considered while planning to set up their LMMA and the challenges they faced. The most common finding: many community members were driven to engage in the establishment of LMMAs for the benefit of their children. They knew the importance of conserving their fisheries if the same resources were to support them and future generations.

Setting up locally managed marine areas was not without its challenges and the illegal turtle fishing incident was a clear indication of resistance to these efforts. Through our interviews we learnt that events of resistance and unfair sharing of benefits can often lead to conflict within and between villages. This could be the cause for reduced engagement in resource management. With a trusted mechanism for conflict resolution, there is the potential to encourage more communities to engage in natural resource management and potentially adopt conservation initiatives.

As we finished our survey with the four communities, I was confident that they would succeed in managing their own resources and increase community engagement towards this common goal. Supporting community focal points like Joazandry and networking LMMA together through MIHARI will help to build a national movement to help drive adoption and success of LMMA across the country and beyond. I am happy to have been part of this process, documenting the findings that will be used as key learning for future approaches with communities in conservation.

Please read more about the study and its findings.

This work was supported by the Natural Environment Research Council and Margaret A. Cargill Philanthropies via the Alliance for Conservation Evidence and Sustainability.

By Hope Beatty. Hope is our Technical Social Research Advisor and is responsible for providing technical support in social science and research within field programmes, outreach, and M&E teams.